Context Matters

If helping feels good, as I’ve written about elsewhere one could reasonably ask why the world so often feels so unhelpful and self-absorbed. If helping feels good, why don’t more people help more often? We tend to blame character or upbringing or something within the person (“They’re just like that. We, of course, have better values.”). But when we focus only on character, we overlook one of the strongest findings in psychology: most of the time, the situation matters more than the person. When we understand this, the path to increasing helping behavior becomes not only simpler, but more promising as well.

We often imagine that our choices about how to behave come from something inside us, a kind of moral compass each of us carries. So when people fail to help, or are rude, competitive, or aggressive, we assume the issue lies in their character. Decades of research, however, suggest a more humbling view. Our behavior is shaped less by who we are and more by the situation we find ourselves in. Tiny cues in our environment are constantly influencing how we act, often without our awareness, which is precisely why we overlook them.

Little things make a big difference

This is not to say that character doesn’t matter. It does. But context matters too, and often more than we like to admit. A small change in what we see or feel can shift what we do. Hundreds of studies show that everyday behavior bends in response to tiny, often invisible cues. Reading words associated with the elderly (Florida, gray) makes us walk a bit slower. Other primes can make us feel smarter or duller, try harder or give up more easily, and of course be more likely to buy a certain brand of detergent or wine. These effects may sound small, but they show how our days are filled with subtle inflection points, and how easily those moments can shape how we move through the world.

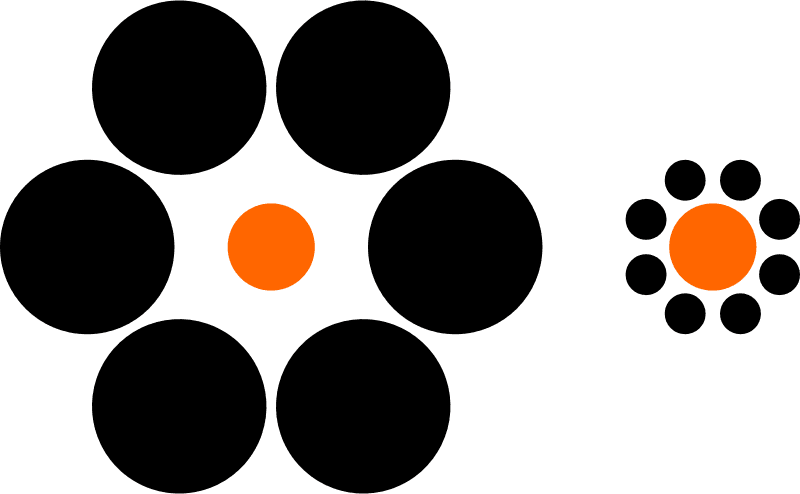

The same sensitivity to context shows up in how we treat one another. Small cues can nudge us toward simple acts of civility. Seeing someone hold a door open makes us more likely to do the same. Reading words or seeing images associated with politeness makes us more polite (or at least less likely to interrupt someone who is speaking). Even painting an image of a baby’s face on storefront shutters reduced vandalism in one neighborhood, presumably by subtly activating a basic caring instinct that all of us have, even those of us who vandalize storefronts.

Context also shapes whether we approach others cooperatively or competitively. In one study, people played an investment-type game with someone else. One group was told it was called the Community Game, while another was told it was called the Wall Street Game. People who played the Community Game opened with a cooperative move, which prompted cooperation from the other player and generated more cooperation (and more money) all around. When it was called the Wall Street Game, players began competitively, and the whole exchange shifted with it, each person becoming increasingly competitive. (Which world are we primed for?)

Our willingness to help follows the same pattern. Toddlers who see two dolls turned toward each other are several times more likely to help spontaneously than when the dolls are turned away or shown alone. Being primed with examples of helping makes us more likely to step in, and feeling like we have time makes us far more likely to help. All of these examples point to the same idea: helping depends not only on intention and character but on the cues that surround the moment.

What This Means for Us

When we recognize how strongly situations shape our willingness to help, it becomes clear that we need to design our environments with that in mind. If we want people to be kinder, more responsive, and more connected to one another, then the settings we create in schools, workplaces, and communities need to reflect the power of tiny contextual cues. This includes designing situations that make helping easy, making it personalized, and giving people concrete opportunities—ideas I explore elsewhere.

Importantly, this also calls for a bit of humility. None of us is as independent from our surroundings as we like to think, and the urge to help is far more universal than we assume. We have to recognize that, embrace it, and build more situations that bring out our better sides.